Mama, am I bilingual or bicultural? Or am I both?

Bilingualism and biculturalism are related, but they are not the same thing.

Some people assume that if you raise a child to be bilingual, that child will automatically have access to another culture. While it helps, it’s not quite that easy — bilingualism is more of a door into biculturalism.

First, the definitions:

- Bilingualism is the ability to communicate in two languages. It generally implies writing, reading, and speaking fluently, although the term is also sometimes applied to individuals who are only bilingual speakers, and not literate in a second language.

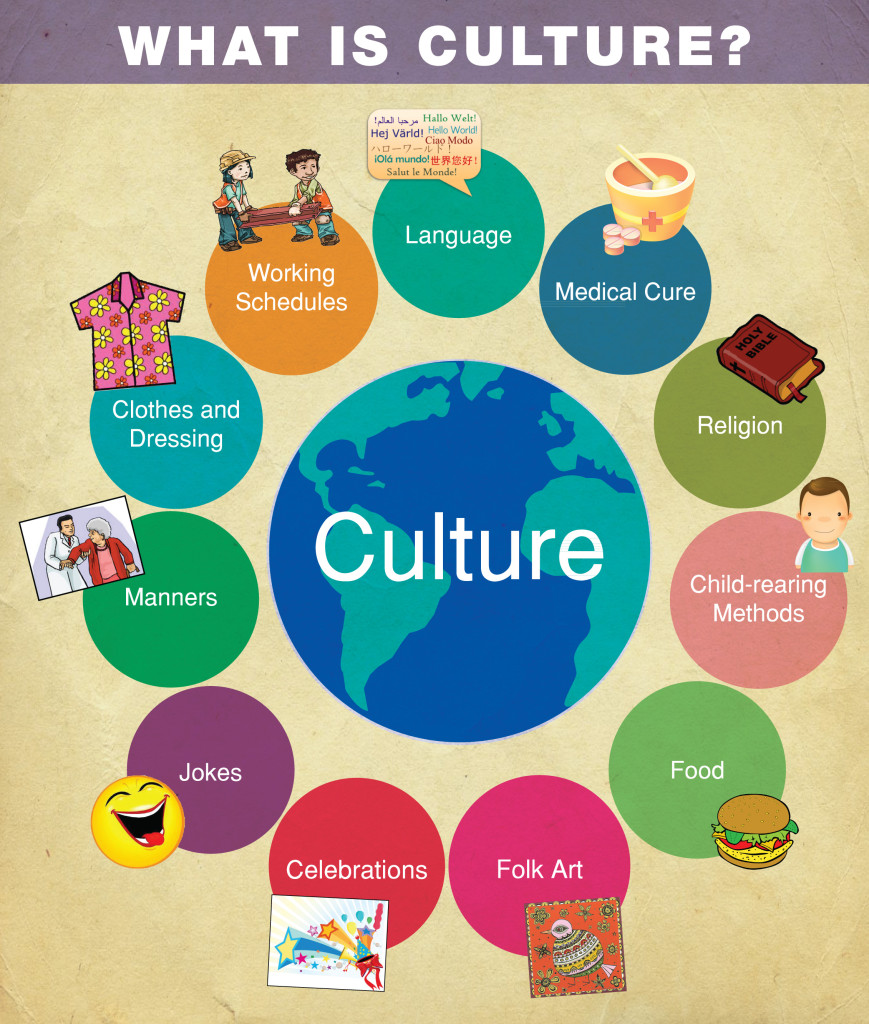

- Biculturalism is an immersion in two distinct cultures, implying participation in traditional heritage practices like food, dress, family traditions, folklore and folk art, etc.

Speaking a heritage language is often an important part of biculturalism. However, the immersion goes beyond that. Biculturalism is often, but not always, the product of a bicultural family, usually one made from a cross-cultural marriage.

Bilingual individuals will have an easier time sampling experiences from other cultures even without a family tradition of it, however — the second language gives them access to people from that language’s culture or cultures.

Aspects of Culture Beyond Language

Here are a few of the things a bicultural individual experiences from more than one perspective, in addition to language and speech itself:

1. Food

Typical Ukrainian celebration. What is on your table?

Cultural or “heritage” dishes are generally influenced by the staples that were available wherever that particular culture and language was established.

Dining cross-culturally can be a linguistic experience — most Americans, for example, know that “con arroz” means “with rice” in Spanish, simply from the prevalence of Latin American foods in the United States.

However, it is possible to eat culturally-influenced meals without knowing any of the parent language, and many children do, particularly in households where immigrant parents or grandparents cook, but children are raised speaking the local language.

Some traditions go beyond just the kinds of food used, and affect how they are eaten as well — the difference between using chopsticks and forks, for example, or between eating omelets and other egg dishes for breakfast (United States) and for evening meals (Eastern Europe and parts of Latin America).

One of the advantages of introducing children to bicultural eating as well as language when they’re young is that it becomes less of a culture shock when they travel later in life. They’re already familiar with the traditional foods of their heritage country. And, as an added bonus, it gets them used to the idea of a varied diet in general — a good way to help discourage picky eating habits!

2. Folk Art

The broad category of “folk art” includes music, dance, folklore, and traditional cultural crafts.

Some cultures have very specific and guarded ones — Japanese flower arranging and calligraphy, for example. Others are practiced all over the world in different styles, such as pottery or even things as common as painting and stringed instruments.

Exposing a bilingual child to cultural art as well can be useful in a couple of different ways. Obviously, it gives them something to appreciate that they wouldn’t normally encounter, but it can also open up new vocabulary, and it can be very revealing about a culture as well. Something as simple as listening to a piece of music by a Russian composer and then one by a contemporary German composer gives even a casual observer a good understanding of some of the differences between the two cultures.

3. Celebrations

Children like this one, because it usually means at least twice as many holidays in the household!

Bringing in holidays from other culture is a start to explaining everything from religious plurality to the differences in calendar systems.

It’s also good motivation, especially when you can explain that Russian-speakers have their own Santa, who only brings presents for Russian-speaking children. You’ll be amazed how prolific the Russian use gets around Christmas time…

4. Jokes

Humor is very difficult to translate.

Even after years of living together, bicultural couples can struggle to understand one another’s humor. But don’t let that difficulty scare you away from it — instead, ask to have jokes explained, and work through why they’re funny in their original cultures. If you understand a culture’s humor, you’re very well-immersed!

Introducing children to multicultural humor is surprisingly easy. Most toys, books, and TV shows marketed toward kids is humor-based already. If you want to give them a grounding in another culture’s humor, just let them watch some silly cartoons — the things that culture finds amusing will become apparent very quickly. You may even learn something yourself.

5. Manners

Teaching manners in just one culture can be a challenge.

You may need to wait until children are older to start explaining to them some of the differences between what separate cultures find polite.

It can be important to go over multicultural manners, especially if you travel, however. For example, Americans tend to smile at strangers as their default — if you make eye contact, you smile, and sometimes nod or even speak a greeting. In other parts of the world (including Russia and Ukraine), strangers tend to avoid acknowledging one another except when they actively interact.

Children don’t always understand the differences, and you may need to do some explaining to make sure they aren’t feeling slighted or punished simply by being immersed in a culture that doesn’t interact the way they’re used to.

6. Clothes and Dressing

Apart from “heritage festivals,” most countries have globalized their fashions to at least some degree. We may know what a culture’s traditional clothing used to look like, but the reality is that most Japanese people do not wear kimonos every day, nor do Germans wear lederhosen and dirndls.

I don’t dress my girls in traditional Ukrainian clothing everyday, but whenever I do – they feel special connection to their heritage culture.

That said, even in countries that share a basic wardrobe (such as the Western business dress used in North America and Western Europe), standards and fashions can vary widely. Most Continental Europeans find Americans extremely sloppy in dress, while sharp-dressed Americans tend to see their British counterparts as too stuffy and the Europeans as too fashion-forward.

Children are usually better off when they’re dressed in the dominent costume, rather than in heritage clothing, at least when they go to school. Save other cultural clothing for special occasions, or for travel.

7. Working Schedules

This usually affects the parents more than the children, but different countries and cultures have very different approaches to work schedules.

The United States tends to be early-rising, with a strong urge to end the workday by 5:00 or 6:00 PM, while Europeans often start and end later. Spanish and Latin-influenced countries share the “siesta,” an hour or two of time off in the middle of the day. And nearly every country has better vacation time for workers than the United States — an unfortunate burden for U.S. parents.

Your children will adapt to your schedules, so if you want them to experience bicultural work patterns, you may need one parent to be on one schedule and the other on another. If this is inconvenient or impossible for you, you may not get to include them in that aspect of biculturalism except on vacations and during other travel.

8. Child-rearing Methods

Battle Hymn of The Tiger Mother made Chinese-American childrearing practices (at their most extreme) famous in the United States last year.

It was a good example of how different perspectives can be from one culture to the other. Not every Chinese mother is Amy Chua, of course, and not every U.S. parent is the permissive caricature she was reacting against.

But it certainly is true that families see children in very different roles depending on culture. In some counties and cultures children are viewed as adults-in-training from birth, while in others they are encouraged to have a long and responsibility-free childhood.

Even the concept of “adolescence” can vary dramatically, with some cultures treating children as adults from sexual maturity onward and others accepting a long “teenage” period of increased intelligence but continuing dependence.

You should find the parenting method that works for you, of course, whether it comes from a heritage culture or not. But when your children inevitably bring up “so-and-so’s parents do things this way” (usually as a complaint because you’re not doing it that way), it can be an opportunity to talk about different cultures of child-rearing.

The Case of the Japanese Brazilians

The back-and-forth migration of the “Japanese Brazilians” is a fascinating example of the differences between biculturalism and bilingualism.

A major move from Japan to Brazil occurred in the early 20th century, when the collapse of feudalism in Japan and a labor shortage on coffee plantations in Brazil led to a treaty between the two governments encouraging immigration.

For a long time, the Japanese population in Brazil remained insular, with Japanese-language schools for the first generation of children born in Brazil. Marriages were predominantly between Japanese immigrants, with very little crossover into the Portugese-language culture of Brazil.

When the Japanese economy began to expand in the 1970s and 1980s, a population of first- and second-generation children of the original immigrants returned to Japan, mostly to factory jobs.

Although they had been raised speaking Japanese as their first language, the Japanese-Brazilian immigrants did not assimilate. The “dekasegi” (a word that originated in Latin American Japanese culture, not in Japan) were viewed by the Japanese as outsiders with gaijin ways, and ended up living predominantly in ethnic enclaves with their own separate cultures and celebrations despite the shared language.

The Japanese government is currently trying to encourage dekasegi to return to Brazil. Migrants with Latin American citizenship have been offered 300,000 yen (about $3,000) to move back to their country of origin, with the condition that they do not re-apply for a Japanese visa or citizenship at any later date.

Many have remained anyway, and both the Portugese language and Brazilian celebrations of culture are now more common in Japan than anywhere else in the world except Brazil itself. Carnival is a major event in dekasegi-heavy cities like Oizumi, and there are multiple Portugese-language newspapers and radio stations.

The dekasegi are a fascinating example of what happens when a large population is raised bilingual but not bicultural. The Japanese-Brazilian culture was sufficiently different from Japanese culture that the returning immigrants found themselves “outsiders” despite their shared language.

It’s also an object lesson in the changes that happen even to fairly insular immigrant groups. The original Japanese settlers in Brazil did not go out of their way to assimilate, but over time their “Japanese” mannerisms became sufficiently different that they no longer blended in with society in Japan itself.

When you raise a child bilingual, that in and of itself does not make the child a part of any heritage culture, even if he or she is descended from immigrants. Bilingualism is a great tool and a way to open the door to biculturalism — but it’s not the same thing!