One thing that often alarms the parents of bilingual children is when their children start switching back and forth between languages mid-sentence.

This has been misunderstood and mischaracterized as a sign of “confusion” on the part of the child.

Both popular culture and older academic literature will tell you that mixing languages is a bad habit. You may encounter teachers who still believe this, and will bring it to your attention as a concern.

Take comfort — the old-fashioned critics are wrong. The most recent literature tells us that most mixed use of language is a natural and positive development in bilingual learners.

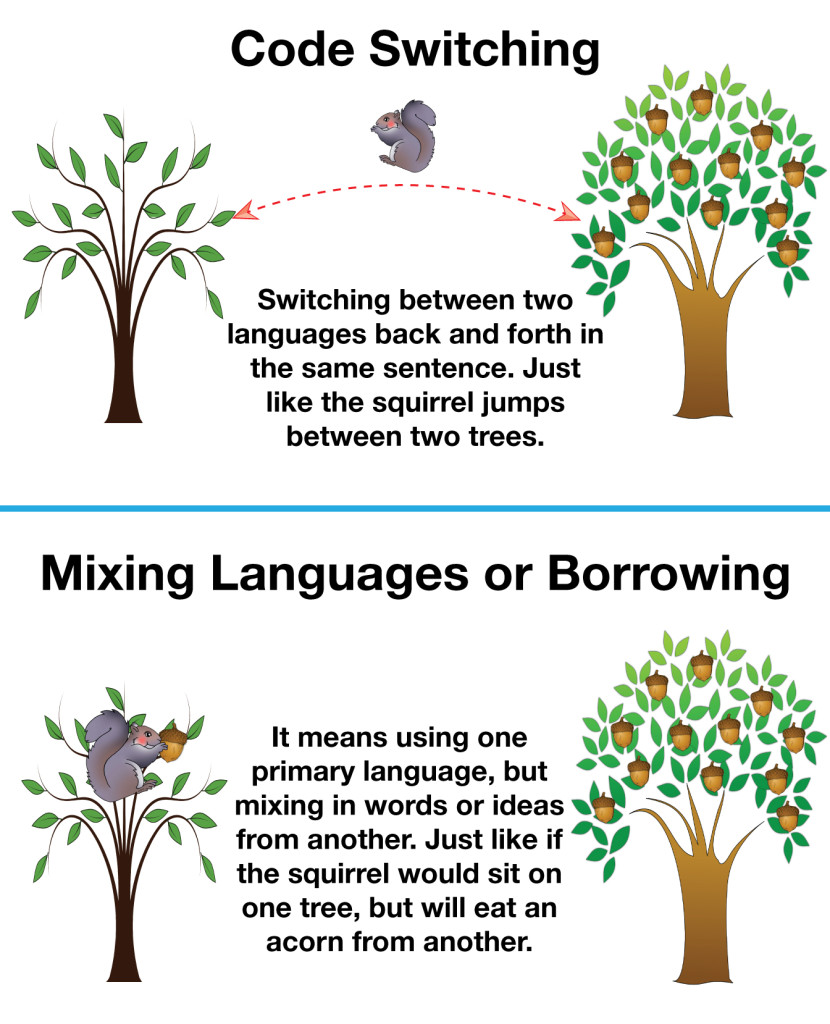

There are two major types of mixed language use: code-switching and borrowing, or “mixing languages.”

Code-Switching

When a child (or an adult) switches back and forth between two languages in the same sentence, using both with fluency, it is called “code-switching.”

This means that the speaker is actively using both languages. He or she is, in effect, thinking bilingually, and using all the available language skills for self-expression.

If a German/English bilingual child were, for example, to say “Mom, can we go auf Urlaub to Florida this year, bitte?” it would be true code-switching — the child is using not just vocabulary but also grammar and syntax from both languages. Both the English and the German expressions for “going on vacation” are used back-to-back.

This is generally not done in excitement or confusion, but rather when the child feels comfortable in both languages. Bilinguals are much less likely to code-switch around people who they do not recognize as sharing their languages.

So while you may hear your child code-switch regularly, this is mainly because your child recognizes your household as a bilingual environment. It is much less likely to happen at school (if your child’s school is monolingual).

Borrowing or Mixing Languages

Code-switching is the use of two separate languages back to back.

Borrowing, on the other hand, means using one primary language, but mixing in words or ideas from another. In borrowing, the child speaks one language, and alters vocabulary from another to fit the primary language.

This is frequently done when a bilingual speaker lacks the exact word for the concept he or she wants to express in the language being used at the time.

For example, a fluent French speaker is likely to use English words, altered into French, when speaking about computing concepts that developed in English first: “Avez vous un point d’accès Internet” simply takes the concept “an Internet access point” and makes it fit into French. This is borrowing, rather than code-switching. The speaker is not really thinking in English, but simply taking vocabulary from it for efficiency’s sake.

Even non-bilinguals do this fairly regularly. An English-speaking chef would feel comfortable referring to his mise en place rather than taking the time to explain “the system by which I arrange my ingredients and tools,” and many gourmands use the Japanese adjective umami without explaining that they mean “a hearty-salty savory flavor.”

As with code-switching, this does not indicate confusion on a child’s part. It actually shows good linguistic skill — the child is using the most appropriate word for a situation. Sometimes the word happens to come from a second language, that’s all.

What To Do About Code-Switching or Borrowing?

Part of raising a bilingual child is accepting that they’re going to use both their languages. That was the whole point!

That means that, from time to time, your child is going to use both languages in combination with one another.

Don’t panic when it happens. It doesn’t mean your child can’t tell the difference between the two languages.

But even with full understanding that code-switching and borrowing is normal, I am still steering my children towards talking to me in monolingual mode (Russian please!). I correct them and ask to repeat in Russian (in a very gentle and friendly manner) because if I let them switch with me – they will soon lean heavily into English, our majority language.

From the other side, if you have a good community of monolingual people in your minority language (let’s say grandparents, aunts and uncles, school, church etc) then your child will frequently find himself in monolingual mode (witch id great!) and not so many corrections will be needed from your side. The only time to offer a correction (a gentle one) is if a child is mixing languages when speaking to someone who doesn’t understand both languages.

How do you deal with your child’s code-switching? Please share you ideas below in the comments – it will help all of us raise our bilingual kids!